Nodens is in an ancient British god of hunting/fishing, water, the weather, healing, and dreams. ‘Nodens’ has been translated as ‘the Catcher’ and ‘Cloud-Maker’, and ‘Deus Nodens’ as ‘God of the Abyss’ and ‘God of the Deep’. The latter links him with Annwfn, ‘the Deep’, the underworld. The nursery rhyme name for the dreamworld, ‘the Land of Nod’, derives from ‘Nodens’.

Nodens is a god of the subliminal realms beneath the everyday world and their hidden processes. This is suggested by the imagery of his Romano-British dream-temple at Lydney. In the centre was a mosaic depicting two blue and white sea-serpents with intertwined necks and striking red flippers. William Bathurst likens them to the icthyosaurus, ‘fish lizard’, of the late Triassic and early Jurassic whose remains have been found across Europe and Asia.

The mosaic also depicts numerous fish, possibly salmon, which would fit with salmon fishing on the river Severn, which the temple overlooks, and the legend of the salmon of Llyn Lliw carrying Arthur’s men up the Severn to Gloucester to rescue Mabon.

An inscription on the mosaic reads: ‘D(eo) N(oenti) T(itus) Flavious Senilis, pr(aepositus) rel(oqiatopmo), ex stipibus possuit o [pus cur]ante Victorio inter[pret]e.’ ‘The god Nodens, Titus Flavious Senilis, officer in charge of the supply-depot of the fleet, laid this pavement out of money offerings; the work being in charge of Victorious, interpreter of the Governor’s staff.’ It has been argued Victorio inter[pret]e, ‘Victorious, interpreter’ was an interpreter of dreams.

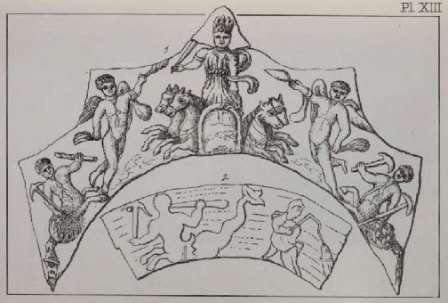

Another artefact found in Nodens’ temple was a bronze plaque from a priest’s ceremonial headdress. Nodens rides from the deep on a chariot pulled by four water-horses. He wears a crown, carries a sceptre in his right hand, and a sea-serpent is looped around his left arm. Flanking him are two winged wind-spirits and two icthyocentaurs, ‘fish-centaurs’ or ‘centaur tritons’, with heads and chests of men, front hooves of horses, and tails of fish. They carry hammers and anchors. Beneath is another icthyocentaur with a hammer and chisel and a fisherman with a short tail and gills hooking a fish, which could be a salmon.

All of this imagery is suggestive of the deep: rivers, the sea, and the depths of the dreamworld/underworld where prehistory gives birth to myth and the boundaries between species break down.

Pilgrims came to Lydney for dream-healing. They would arrive at the guesthouse, bathe in the baths, then make offerings to Nodens through a funnel in his temple (which suggests he dwelled below in the deep). They would then retire to a long row of cells to enter a sacred (likely drug-induced) sleep during which they would receive a vision from Nodens. The dream-interpreter would listen to the dream then suggest a method of healing based on Nodens’ message.

Offerings included coins and several beautifully crafted bronze hounds. It is likely dogs were present to lick the wounds of the injured to aid in the healing process. They may also have acted as psychopomps guiding the sleepers through the dreamworld. The son of Nodens/Nudd, Gwyn ap Nudd, had a red-nosed dog called Dormach with two serpents’ tails.

***

Nodens’ temple was built on an iron ore mine and he was known as ‘Lord of the Mines’. This may explain the hammers and chisels carried by the icthyocentaurs. Mines are associated with the chthonic depths of the underworld and its riches, which are often guarded by serpents.

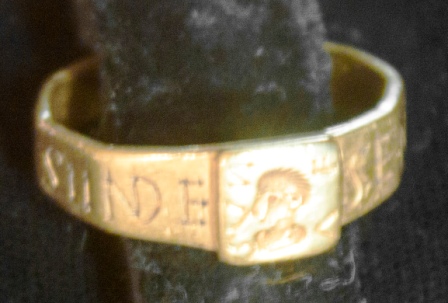

Intriguingly a man called Silvianus vowed half the worth of a 12g golden ring to Nodens in exchange for withholding health from its thief, Senicianus, until it was ‘returned to the Temple of Nodens’. The ring was dug up in a field in Silchester in 1785 with a new inscription: Seniciane vivas in deo, ‘Senicianus, may you live in God’. What was originally inscribed on it remains unknown. It seems possible it served a ritual function in Nodens’ temple.

In ‘The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’, Gwyn states ‘I have a carved ring, a white horse gold-adorned’. His ring is an important part of his symbology and might have been a gift from his father. Angelika Rüdiger links its circularity with the ouroboros.

The ouroboros first appears in ‘The Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld’ in the ancient Egyptian Funerary text KV62, which focuses on the union of the sun-god Ra with Osiris, god of the underworld. In an illustration two serpents with their tails in their mouths coil around the unified Ra-Osiris. The image represents the beginning and the end of time.

The ouroboros was passed on to the Phoenicians and ancient Greeks who gave it its name. In Greek oura means ‘tail’ and boros ‘eating’, thus ‘tail eater’. The ouroboros appears in most cultures across the world and throughout history.

A pair of sea-serpents are central to Nodens’ temple. He holds a sea-serpent. It seems possible two ouroboros serpents may have been carved on a ring worn by Nodens and passed on to his son, representing their knowledge of the depths of time where beginning and end meet as they bite their tails. Silvianus’ ring may have been a replica of this powerful mythic artefact.

It’s rumoured that Tolkien based his One Ring on the ring from the temple of Nodens and that Nodens, ‘Lord of the Mines’ was a precursor to Sauron, ‘Lord of the Rings’.*

***

In medieval Welsh literature Nodens appears as Nudd/Lludd Llaw Eraint, ‘Lludd of the Silver Hand’. Their linguistic connection is certified by a bronze arm found in the temple of Nodens.

Nobody knows how Lludd lost his arm or how his silver one was made. Parallels might be found with his Irish cognate, Nuada Airgeadlámh, ‘Nuada Silver Arm’, king of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who lost his arm battling against the Fir Bolg. Because of his physical imperfection Nuada was replaced as king by the tyrant, Bres. After Bres was removed Nuada was restored to sovereignty with a new silver arm made by the healer Dian Cecht.

In the story of Lludd and Llefelys, Lludd’s sovereignty is also under threat. Although he is described as ‘a good warrior, and benevolent and bountiful in giving food and drink to all who sought it’ he is unable to defend Britain from three plagues; perhaps this is due to his missing arm.

The first plague is a people called the Coraniaid who cannot be harmed because they can hear all conversations on the wind. The second is a scream every May eve that causes such terror that men lose their strength, women miscarry, youths go mad, and the land becomes barren. The third is the disappearance of the year’s supply of food and drink from the king’s courts.

This story is set during Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 55BC. The Coraniaid are the Caesariad, ‘Romans’ and the other plagues seem linked to the ill effects of their attacks. Lludd, of course, was not a ‘real’ king at that time but a divine ruler of the underworld who may have been called upon by the Britons for aid against the Romans.

Unable to defeat the plagues himself, Lludd is forced to seek the aid of his brother, Llefelys, ‘king of France’. Llefelys instructs Lludd to poison the Coraniaid with insects crushed into water. He then explains the scream: ‘that is a dragon, and a dragon of another foreign people is fighting it and trying to overthrow it, and because of that your dragon gives out a horrible scream.’

Lludd’s dragon represents the Britons and the other dragon the Romans. Lludd, again, is connected with two dragons/serpents. Will Parker has likened Lludd’s dragon’s scream to ‘the scream over Annwfn’, a ‘mysterious ritual frenzy’ uttered by a person threatened with losing their claim to inherited land. It may have originated as an invocation of the spirits of Annwfn to bring about madness and barrenness. Likewise Lludd’s dragon screams as its land is lost to the Romans, blighting all who live there. Lludd has lost control of these chthonic forces.

Llefelys teaches Lludd to put an end to the second plague by a complex ritual process. He must measure Britain, length and breadth, and locate its centre. This omphalos, ‘navel’, turns out to be Oxford. It is of interest that the Greek omphalos, Delphi, was formerly known as Pytho and its oracle, the Pythian priestess, spoke with the aid of the whispering python coiled beneath.

Could Oxford have been the location of a dragon (or dragons) who whispered prophecies from the navel of Britain? Dragon Hill lies 50 miles outside Oxford. Its connections with Uther Pendragon and a dragon-slaying by Saint George are suggestive of an older and deeper mythos.

Lludd is instructed to dig a hole at the centre of Britain then place in it a vat of mead with a sheet of brocaded silk over the top. Llefelys says, ‘You will see the dragons fighting in the shape of monstrous animals. But eventually they will rise into the air in the shape of dragons; and finally when they are exhausted after the fierce and frightful fighting, they will fall onto the sheet in the shape of two little pigs, and make the sheet sink down with them, and drag it to the bottom of the vat, and they will drink all the mead, and after that they will fall asleep.’

This scene depicts the return of the escapee dragons to the omphalos of Britain and the deep. It is intriguing that they are not just dragons but are capable of taking many different forms. It is possible to perceive a mythic and perhaps evolutionary development in their shapeshifting from ‘monstrous animals’ beyond description to ‘dragons’ to two seemingly innocent ‘little pigs’.

Finally Llefelys tells Lludd to ‘wrap the sheet around them, and in the strongest place you can find in your kingdom, bury them in a stone chest and hide it in the ground, and as long as they are in that secure place, no plague shall come to the island of Britain from anywhere else.’

Lludd buries the dragons at Dinas Emrys in Snowdonia. The next time they cause trouble is during the reign of Vortigern. Every time he attempts to build a fortress on the hill it falls down. Merlin Emrys reveals to him that the cause is two dragons battling. The red one represents the Welsh and the white one the Anglo-Saxons.

Llefelys informs Lludd that the food and drink are stolen from his court by a magician who uses a sleep spell. He suggests Lludd step in a tub of cold water to keep himself roused. Lludd defeats the magician in combat, all that is lost is restored, and the magician becomes his vassal.

All three plagues are defeated. The chthonic forces of Annwfn are brought back under Lludd’s control. Caesar’s invasion of Britain fails. Lludd and Llefelys depicts the mythic processes beneath this historical period, which the Druids and seers who interacted with the deities of the underworld might have been aware of and perhaps instigated with prayers and invocations.

Lludd reigns ‘until the end of his life’ ‘in peace and prosperity’. One wonders whether Llefelys had a role in creating Lludd’s silver arm…

It seems Lludd’s ‘kingdom’, Annwfn, the deep, is passed on to his son, Gwyn ap Nudd, whose role is to contain the spirits of Annwfn to prevent them from bringing about the end of the world.

Does Gwyn’s inheritance include the serpents of the deep: beings who are older than gods, whose ‘battles’ may be less about conflicts between groups of humans than the regenerative processes that shape the earth through the aeons, through the beginnings and endings of each world?

***

*Tolkien advised Sir Mortimer Wheeler on his excavation of Lydney in 1938

SOURCES

Angelika Heike Rüdiger, ‘Gwyn ap Nudd: A First and Frame Deity, Temple 13, (Temple Publications)

Caitlin Matthews and Jane Dagger, ‘Temple of Nodens Incubation’ http://www.hallowquest.org.uk/temple-of-nodens-incubation

Elizabeth A. Grey (transl), The Second Battle of Mag Tuired, (Forgotten Books, 2007)

Greg Hill (transl), ‘Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir’ https://barddos.wordpress.com/2015/02/08/gwyn-ap-nudd-and-gwyddno-garanhir/

Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Sylvia Victor Linsteadt, ‘The Return of the Snake’ http://theindigovat.blogspot.co.uk/2017/05/the-return-of-snake.html

William Hiley Bathurst, Roman Antiquities at Lydney Park, https://archive.org/details/romanantiquitie00bathgoog

‘The Forest of Dean and Wye Valley’s Celts and Romans’ http://www.deanweb.info/history4.html

great post 🙂 always wanted to learn more about this guy…

The idea of the Omphalos or the Centre as the portal to the Otherworld is interestingly discussed by Alwn & Brinley Rees in ‘Celtic Heritage’ where they point out that it might a measured place (relative to whatever sense of the whole is being used) such as Uisnech in Ireland or Oxford in the ‘Lludd a Lleuelis’ story, or it might be mo

(Continued from previous as I accidentally hit the post button) …. it might be anywhere, such as Gorsedd Arberth in the Mabinogi or Dinas Emrys in Wales. The worm as the dragon is certainly an attractive comparison. Serpents of the Deep indeed!

Yes I feel like the omphalos could in some ways be an otherworld place accessible from various locations. It’s my intuition that pit Lludd dug with mead in it was originally a well of Awen connected with the dragons… more on that at a later date!

Da iawn, diddorol iawn! Diolch yn fawr!

Serpents and dragons and little pigs… Oh my! The mysteries of the water… the deepest deep… thank you, this is wonderful…

And thank you for passing on the info about the python at the omphalos at Delphi – that was really helpful and I wouldn’t have written this post without it 🙂

Happy to help…. you are a fantastic bard… email in gestation…!

Thanks Lorna, An amazing and informative piece. I love the work you are doing. Some time ago I found myself identifying The Wessex dragon mound with the mound of Narberth. It’s a long story but it seems that the beautiful lady on a white horse riding slowly on the track was the sun. Slow but uncatchable. The Sun was feminine in those times. At the midwinter dawn she rises above the hill figure as seen fron the village below. Where the pub is called the Rising Sun. A while later I saw the Midsummer suset down between the hills either side of the Manger. Its all on a website of mine, down currently, but if you like I could make a copy and send it to you.

Jon Appleton

Ooh how interesting. At Dun Brython we see Epona/Rigantona/Rhiannon as a psychopomp who leads the sun to rebirth over the period from Eponalia 18th Dec – 23rd Dec. Yes do send me a copy to lornasmithers81@gmail.com

I thought the omphalos of Britain was a phone box in the Forest of Bowland? 🙂

I’ve long thought of Bill Caddick’s John O dreams as good song to sing in honour of Nodens. I realise now that his ‘Cloud Factory’ may also fit…

I hadn’t heard these before and like ‘Cloud Factory’. I bet it would be pretty cool singing it up at Lydney if you had the chance to visit again 🙂

one day…

on the matter of serpents of the deep I kept on thinking of those ram horned serpents which are found all over the Gundestrup Cauldron, particularly visible with the figure of Cernunnos. There is a connection in the image of the serpent it seems with very deep and old powers working away in the mysterious depths. Powers far older than us and full of magic. I wonder with the ability of serpents to slough off their old skins that this was perceived in connection with the Celtic belief of their dead being reborn in Annwn through the goddesses cauldron, this cyclic passage of the soul akin to the Ouroboros circular ring shape….the one ring Nodens wore? In the Dragon Queen by Alice Borchardt there are sea serpents whch in her version of post Roman Britain speak with the main character Guinevere who has a kind of psychic bond with them.

Yes… I also connected the serpent on Nodens’ arm with the serpent held by Cernunnos. I’ve often wondered if Cernunnos, Gwyn, and Pen Annwfn, keeper of the Cauldron of Rebirth, are the same person under different titles. Maybe the animals surrounding him on the Gundestrup Cauldron, particularly the person on the fish, depict a variant of the rebirth of Mabon, in whose abduction he might have played a role?

I hadn’t thought of the sloughing off of serpent skins as representative of the process of the cyclic passage of souls, but what would certainly fit – thanks for that 🙂