A few weeks ago I visited Edinburgh. This was partly due to my interest in its history as part of the Old North. During this period it was known as Din Eidyn ‘fort of Eidyn’ (Eidyn’s identity and whether this name refers to a person and/or place remain a mystery).

There is evidence of settlements on Castle Rock and Arthur’s Seat from the Bronze and Iron Ages. The earliest fort was known as ‘The Castle of the Maidens’. It may have been established on a pre-Christian site sacred to ‘the nine maidens’ amongst whom was Morgen: a divinity connected with water, shapeshifting, healing and the weather.

During the Iron Age the local tribe were known as the Votadini. It has been argued this name originates from the early Celtic *wo-tādo, which means ‘foundation’ or ‘support’ and that this was the name of an ancestral figure. During the Romano-British period, the Votadini became known as the Gododdin and their kingdom was Manaw Gododdin.

Like many of the northern British peoples, the Gododdin had complex relationships with Wales. Sometime between 380 and 440, Cunedda, a man from Manaw Gododdin, helped defend north Wales from the Irish and played a prominent role in founding the kingdom of Gwynedd, which his offspring ruled.

After the death of Cunedda’s descendant, Maelgwn Gwynedd in 547, Elidyr Mwynfawr, who was married to Maelgwn’s daughter, Eurgain, travelled from Benllech in the North via the sea* to Benllech on Anglesey to contest the claim of Maelgwn’s illegitimate son, Rhun, to the throne of Gwynedd. Elidyr was killed at Arfon.

Afterward, Clydno Eiddyn, who may have ruled Din Eidyn, formed part of a warband alongside other northern rulers; Nudd Hael, Mordaf Hael and Rhydderch Hael. Seeking vengeance for Elidyr’s death, they travelled to Wales, set fire to Arfon and were driven back all the way to the river Gwerydd (the Forth).

Clydno was also the keeper of one of ‘The Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain’ ‘which were in the North’: ‘The Halter of Clydno Eiddyn, which was fixed to a staple at the foot of his bed: whatever horse he might wish for, he would find in the halter.’

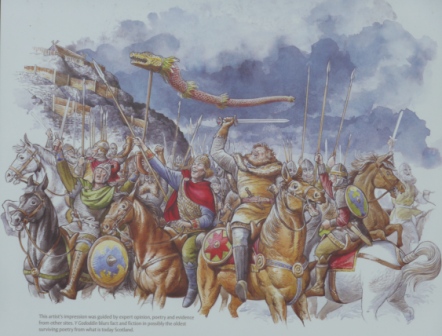

The Gododdin are immortalised in the poem The Gododdin, which has been dated to the 7th century. This takes the form of a series of verses eulogising and elegising the northern Britons who perished in the battle of Catraeth** in 600AD fighting against the Bernician Angles. Prior to the battle, the warriors feasted and drank for a year in the hall of Mynyddog Mwynfawr, ruler of Din Eidyn. The joy of the mead-feast is repeatedly contrasted with the bloodshed of the battle from which ‘of three hundred, save one man, none returned.’

‘Warriors went to Catraeth with the dawn,

Their ardours shortened their lives,

They drank mead, yellow, sweet, ensnaring,

For a year many a minstrel was joyful.

Blood-stained were their swords, may their spears not be cleansed;

White were the shields and square-pointed the spearheads

Before the retinue of Mynyddog Mwynfawr.’

Cynon, a son of Clydno Eidyn was amongst the casualties and is the subject of several verses.

‘…generous-hearted Cynon, lord of graces…

Whomever he struck would not be struck again.

Sharp-pointed were his spears,

With shattered shields he tore through armies,

His horses swift racing forward.’

‘He slew the enemy with the sharpest blade,

Like rushes they fell before his hand.

Son of Clydno of enduring fame’

The imagery of The Gododdin is strikingly similar to that of The Conversation of Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir. In The Conversation, Gwyddno addresses Gwyn as a ‘bull of battle’ and says ‘armies fall before the hooves of your horse / As swiftly as cut reeds to the ground’. Gwyn speaks of ‘shields shattered, spears broken’ and states his presence at the deaths of a number of northern warriors ‘where ravens croaked on gore’.

In The Gododdin, two warriors are referred to as ‘bull(s) of battle’, one as ‘bull of an army’ and another as ‘heroic bull’. Men are hewn down ‘like rushes’, there are countless references to ‘shattered’ and ‘splintered’ spears and shields and the dead become ‘food’ for ‘ravens’. This suggests both poems originated from the same milieu. It seems possible Gwyn gathered the souls of the dead after the battle of Catraeth as he did after the battle of Arfderydd in 573.

When I visited Edinburgh Castle, I was struck by the height and impenetrability of the cliff face (Castle Rock was originally a volcano which was later flattened by a glacier) and could see why it has been a defensive location for so long.

Unsurprisingly, after so many centuries, there were few traces of the Gododdin. The castle was built in stone in the 12th century and the current banqueting hall during the 15th. The hall has a prominent hearth fire and is decorated with spears, swords and armoury. It’s possible to imagine Mynyddog Mwynfawr’s hall would have been equipped in a similar manner.

Since Catraeth, Edinburgh’s people have seen countless bloody battles, including the Wars of Independence from 1296 and 1341, the ‘Lang’ siege which lasted from 1571-1573 and the Jacobite Risings from 1688-1746. The castle was later used as a military prison. It is still a barracks and is now home to the Scottish National War Memorial: an extensive ‘shrine to the fallen of two world wars and campaigns since 1945’.

As a metaphor for tragic and ill-conceived warfare, ‘drunken Catraeth’ may be seen to repeat itself throughout history. A. O. H. Jarman notes ‘a veteran of the action of Mametz Wood during the battle of the Somme in 1916 ‘recalled an observer saying what a magnificent sight it was seeing the Welsh battalions moving along in a line without wavering until they fell’… His observation could have translated a couplet of Y Gododdin.’

In ‘Elegy for the Welsh Dead in the Falkland Islands, 1982’, Tony Conran draws analogies between Catraeth and the Falklands War:

‘Men went to Catraeth. The luxury liner

For three weeks feasted them…

With the dawn men went. Those forty-three,

Gentlemen all, from the streets and byways of Wales,

Dragons of Aberdare, Denbigh and Neath –

Fragment of Empire, whore’s honour, held them.

Forty-three at Catraeth died for our dregs.’

Beneath Din Eidyn I read my poem, ‘Lamentation for Catraeth’, which is also based on lines from The Gododdin: ‘By fighting they made women widows, / Many a mother with her tear on her eyelid’. Written in the voices of mourning women, it laments ‘drunken Catraeth / the battle that knows no end’.

***

*This is recorded in the triad of the Horse Burdens where Elidyr and seven-and-a-half men (one holding onto the crupper!) are carried by the legendary water-horse, Du y Moroedd.

**The location of Catraeth is hotly contested. Traditionally it has been identified as Catterick, yet so far no evidence for a full-scale battle has been found. Tim Clarkson notes the identification of Catraeth with Catterick is based on a ‘sounds like’ etymology’ and suggests the conflict was more likely to have taken place on the fringes of Lothian.

SOURCES

John Matthews (ed), The Book of Celtic Verse, (Watkins Publishing, 2007)

Heron (transl), Gwyn ap Nudd and Gwyddno Garanhir, HERE

Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson (transl), The Gododdin, (Edinburgh University Press, 1969)

Peter Bartrum, A Welsh Classical Dictionary: People in History and Legend up to about A.D. 1000, (National Library of Wales, 1993)

Rachel Bromwich (ed), The Triads of the Island of Britain, (University of Wales Press, 2014)

Stuart McHardy, The Quest for the Nine Maidens, (Luath Press, 2002)

Tim Clarkson, The Men of the North: The Britons of Southern Scotland, (John Donald, 2010)

Votadini, ‘The History Files’, HERE

Thanks for this informative piece. This time of year seems to inspire accounts of the war dead. Well done!

Alas, the militarisation of culture -and of masculinities in particular- goes back a long way. Sadly these are unlikely to be the last such romanticising (?) elegies. Reading this made me want to reach for some political/cultural criticism. Bob Connell’s critique of sexual ideology -‘the regulation and management of gender regimes’ came to mind. He argued that ‘the imaginative literature of combat’ have been pivotal to the construction of hegemonic masculinity. As you’ve been pointing out elsewhere, how these histories are retold, and marked, may be of vital importance.

Good to see Tony Conran’s poem being quoted here. As a translator he knew this material from close engagement with it. As a poet he transformed it into his own powerful commentary on modern warfare, both a tribute to those who died in the manner of ‘ YGododdin’ and also an incisive indictment of the futility of the conflict. I know he was passionate about this poem and it was moving to hear him read it on more than one occasion.

Man sollte auch derer gedenken die unter den Kriegen leiden ohne kämpfen zu können und die nicht entscheiden was geschieht

Ich beschäftige mich seit langem mit dem Y Gododdin Ich bin besonders an den nachträglichen Ergänzungen im Y G. interessiert und habe eine Theorie zur Urheberschaft einer dieser Ergänzungen aufgestellt und diese beim grin- Verlag als E-book veröffentlicht. Leider derzeit nur in Deutsch.